Ali the Greatest

0By The Spotter

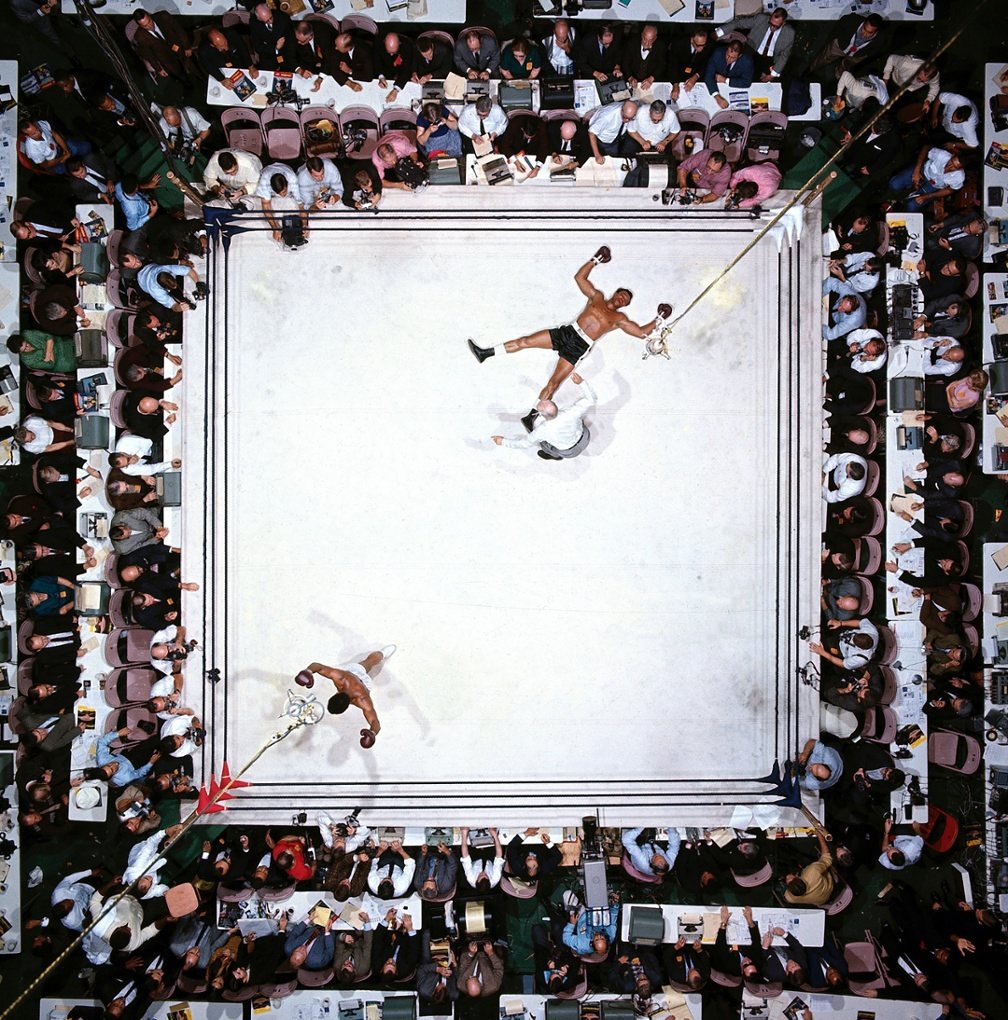

A force of nature and the personification of charisma, it was Muhammad Ali’s exploits as a boxer and champion in the heavyweight division on three separate occasions that was the bedrock of his great fame.

A force of nature and the personification of charisma, it was Muhammad Ali’s exploits as a boxer and champion in the heavyweight division on three separate occasions that was the bedrock of his great fame.

Ali was, quite simply, the greatest- a moniker which became a part of his most famous catchphrase: “I am the Greatest”. A phenomenon who was to become the most widely-known sporting figure of all-time across the globe. Try mounting an argument against that and you probably won’t get very far, or else you are perhaps just a bit too young.

His enduring reach and legacy wasn’t of course just through a magnificent prowess in the ring. He was also a figurehead and champion of the Civil Rights movement for racial equality in the U.S.A., which finally gained real impetus from the early 1960s. The articulate, confident Ali was a perfect foil for the tireless Martin Luther-King Junior, in promoting basic human rights for African-Americans, especially in the Deep South.

Muhammad Ali was born Cassius Marcellus Clay in Louisville, Kentucky on January 17, 1942. From the inglorious beginning of being christened with a name derived from a slave-owning senator of the pre-civil war American south, Ali took up boxing after having his bike stolen as a child.

He was to become known as ‘The Louisville Lip’ on account of his clever wit and his rhyming put-downs of hapless opponents, which were often delivered with a lot of finger-pointing and a wide, wild and mischievous glare straight down the barrel of a camera. Here then, are a selection of Ali-isms from the man himself:

He was undoubtedly a great champion, but also a great polariser. It came as no surprise to anyone around in the U.S. in the 60s that his confidence and boastfulness used to rile and literally infuriate many middle-class and mainly white (and most probably, racist) Americans. This is no better summed up than by this quote from Teddy Brenner, a matchmaker at Madison Square Garden in New York: ‘I could announce that tomorrow Muhammad Ali will walk across the Hudson River and there would be 20,000 down there to watch him. And half of them would be rooting for him to do it and the other half would be rooting for him to sink’.

When Ali refused to enlist to fight in the Vietnam War, uttering the immortal “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong”, there was quite literally a bounty placed on his head by some. He had also converted to the Islamic faith and he stated that as a minister of religion and a conscientious objector he could not advocate going to war. As it was though, he did jail time for his refusal and he was subsequently banned from boxing until 1970.

Ali was always true to his faith however, and was involved in peace activism even when crippled by his failing health from Parkinson’s disease.

ALI IN BOXING

After winning the Light-heavyweight gold medal at the 1960 Rome Olympics, Ali was backed by a group of businessman from his home state and his professional career was launched in conjunction with the trainer that remained with him throughout his career and the one who helped devise the ingenious ‘Rope-a-dope’ plot that sucked in George Foreman in Zaire in 1974, the legendary Angelo Dundee.

In Miami in February 1964, the-then Cassius Clay tormented the previously impregnable and brutal ‘Brown bear’, Sonny Liston with his lightning jab and even faster mouth, and the reigning champ was unable to answer the bell for the seventh round. A new king of the heavyweight division was crowned. Ironically, the unpopular and reserved Liston was forcefully cheered on by the majority of the crowd, who plainly just couldn’t stomach Ali’s brash confidence and bravado- a happening Ali recalled with glee even many years later.

After his ban was uplifted in 1970, Ali had a couple of comeback fights before taking on the pride of Philadelphia (not ‘Rocky’, for goodness sake), ‘Smokin’ Joe Frazier in the so-called ‘Fight of the Century’ (also known as ‘The Fight of the Champions’) on March 8, 1971 at MSG, New York. For the first time in history, two undefeated champions were to compete for the Heavyweight title.

Boxing writer Harry Mullan wrote that they fought ‘for fifteen unforgettable rounds’. Frazier won a points decision and put the exclamation point on his victory with a vicious left hook that floored Ali in the final round.

Ali extracted revenge in their rematch two years later, and then in 1975 the stage was set for the unforgettable third meeting, ‘The Thrilla in Manila’. If there has been a greater fight in Heavyweight boxing history then please tell me, I’d love to know. It was replayed in its entirety recently on ESPN’s Classic Fights series. It is more or less known to be the fight that started to permanently wreck Ali’s health (Ali later admitted that it nearly killed them both), and it is easy to see why. The two of them gave each other such a prolonged pounding. In most bouts, particularly in the heavier divisions, there is usually a hiatus somewhere in the action where the fighters lean on each other and tie each other up for respite, or jockey around the ring for position.

That day though, there was no let up for the whole fifteen rounds- Ali’s jab and combinations confounded Frazier early on, but Frazier just continued coming forward regardless and pummelled Ali with lefts in the middle rounds. Ali somehow regrouped and launched such an assault on the exhausted Frazier that he was unable to make it out for the last round. It was the fight that cemented Ali’s status as an unconditional legend. If the ‘Rumble in the Jungle’ was Ali’s strategical masterpiece, then the ‘Thrilla’ was surely the physical miracle.

I was a wee bit young to recall that aforesaid bout, but I clearly remember watching Ali’s shock loss to the 10-1 outsider Leon Spinks in Las Vegas in February, 1978. I remember saying to my Dad “What happened, he was supposed to win!” He couldn’t really answer, the shock was too great as Ali was a big hero of his. Spinks was no fallguy though- he had won the 1976 Olympic gold in the light-heavyweight division. In the rematch exactly seven months later to the day in New Orleans, Ali found a way even in the very early grip of Parkinson’s, to subdue Spinks, his junior by over eleven years, to be able to reclaim the Heavyweight title for a still unprecedented third time.

Ali’s last major fight was a calamity versus Larry Holmes, then at the peak of his powers. it was an ugly mismatch and should never have taken place. It almost certainly ruined the quality of the rest of Ali’s life, as he was already suffering visible signs of decay in movement and his speech was already noticeably becoming slurred. Ali’s doctor even implored that the fight not be allowed to take place. Unfortunately, the Nevada State Athletic Commission greenlighted the carnage and Ali was knocked senseless, Holmes winning on a technical knock out in the tenth round. That the fight had even made it that distance was a travesty, as Holmes often pulled back from almost killing Ali, at the same time as Holmes’ corner continually begged the referee to step in and end it early. It remains a horrible chapter in the history of world sport and which had lifelong consequences.

MUHAMMAD AND HOWARD

Throughout his career, the totally charismatic and magnetic Ali enjoyed great verbal jousts with a range of sports announcers and interviewers, among them Brits Michael Parkinson and the boxing commentator, Harry Carpenter. But Ali’s best was usually saved for the granddaddy of all American sportscasters, the one and only Howard Cossell. Their bond was just unique. I can’t really explain it to you, so here are some examples

That shuffle in his heyday was just something else also.

(For my Dad and his old school mate Bruce Diver).