Collected Memory: the future of the NZ Sports Hall of Fame

0In the 1990s, I was a sports mad kid growing up in Central Otago, deep in a sports mad country. While we had the opportunity to see Mark Greatbatch get hit by a half-full beer can or listen to Ken Rutherford’s bat rattle around the changing room at Molyneux Park, the big sporting events happened further away from us, usually within Carisbrook’s iconic surrounds.

It was there I saw my first streaker – interrupting a Danny Morrison/Willie Watson last wicket stand for Auckland, my first All Blacks Test – too young for the Terraces, I only remember staring at the backs of old men, and the glorious NPC victory from Otago’s all-time great 1998 side – I still watch the highlights regularly.

For me, Dunedin was the place where a lot of my sporting memories could be collected.

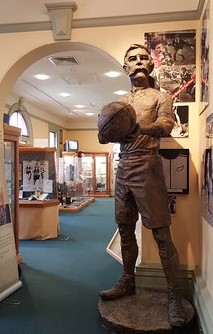

In 1999, the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame opened inside Dunedin’s photogenic railway station. The nation’s sporting memories now collected in the southern city.

—-

Over the last year, the Sports Hall of Fame has, perhaps, been the subject of more column inches than it has since opening weekend. The recent focus started with a review from Sport NZ, the Hall’s major funder, completed in early 2020. While the contents of that report have not been made public, it is believed it focused on the inefficiencies of the current model and recommended a move aligning it with a sporting stadium, not necessarily one in Dunedin.

Although the Sport NZ review, according to reports, highlighted that doing nothing was not an option, it appears nothing was done. That inaction led to the Hall’s Chief Executive, Ron Palenski, signalling, in late 2019, closure was imminent due to a lack of funding.

While the Museum managed to overcome that challenge, it was only a stay of execution. In September 2021, the Dunedin City Council, their secondary financial backer, pulled the pin on their support. The vote was split with Mayor Aaron Hawkins casting the deciding vote.

Complicating matters for all involved, Sir Eion Edgar publicly announced he would be bequeathing $500,000 to the Hall. Edgar’s contribution came with a hitch: the money would be available for the development of the Hall in a defined new location: the Edgar Centre

The Edgar Centre is another triumph of 1990s’ sport, opening in 1995, and has provided an indoor space for a number of sporting and community events since. It is also away from the city and largely serves as a space for casual community sport.

After Edgar’s death in June 2021, Forsyth Barr topped up his half million dollar contribution with $200,000 from their Charity Brokerage Day.

Ian Taylor, another of Dunedin’s favourite sons with strong links to our proud sporting heritage, has become the face of the public debate around the Hall of Fame. He has called out the Council for, what he sees as, their short-sightedness and talked openly about the interactive experience which a new Hall of Fame would offer.

Further up the road, the National Sports Museum Trust of New Zealand are trying to gain a foothold in Christchurch and they have their eyes on the prize: the Hall of Fame. In fact, with the Dunedin City Council casting the Hall’s tether free, the Sports Museum Trust are working to find a spot to relocate the collection while they move through the motions to complete their ambitious project, likely many years away.

—-

All this paints a complicated picture of the situation surrounding the Sports Hall of Fame. You would think, in a nation so often referred to as “sports mad” – including in the opening lines of this piece – there would be more support for the preservation and celebration of our collective sporting heritage.

Sadly, the reality is very different.

From 1998 to 2013, New Zealand had an Olympic Museum. When it closed, a press release promised a “new format” and celebrated the potential sharing of the Museum’s collection with regional museums around New Zealand.

Soon after, the Museum wound up and an attempt was made to offload its collection permanently to other museums.

Te Papa’s passion for our sporting history came to the fore when they purchased a knock-off Peter Snell singlet in 2017. They then made good on the erroneous purchase by creating a small exhibit of items donated by Snell.

That display was set up against the only wall available in Te Papa and hasn’t been seen in the national museum since. Te Papa is an incredible asset to this country, but it can’t keep being all things – it does both Te Papa and our sporting heritage a disservice to assume it can hold McCullum next to McCahon.

In spite of the artistic merits of both.

Our two sporting museums with an extended history of their own have faced unique challenges along the way.

In Palmerston North, the New Zealand Rugby Museum – arguably the museum with the strongest chance of success given its focus – has long adapted and battled to retain a foothold.

With minimal support from NZ Rugby, and regular attempts from that same organisation to create competing experiences in other, more central locations, it’s a testament to those behind it that it remains relevant and continues to develop.

At Wellington’s Basin Reserve, the New Zealand Cricket Museum has sat dormant for nearly three years as the stand it is housed within went through earthquake strengthening and has then had to ride the wave of COVID impacts and delays through to a planned November 2021 reopening.

Much like the Sports Hall of Fame, it has survived on the generosity of the local council in providing it with a space to exist. Unlike the Rugby Museum, it has benefited from stronger funding ties, and fewer competing interests, with its governing body.

It is also entirely unsustainable as a standalone museum without, at least, that level of support.

They all are.

—-

You don’t have to look far to find a more sustainable model for a sporting museum, with Australia’s Sports Museum at the Melbourne Cricket Ground a shining light amongst our antipodean sporting heritage experiences.

Recently redeveloped, the Australian Sports Museum contains interactive displays dedicated to AFL, cricket, the Olympics, and Sport Australia’s Hall of Fame.

It’s not hard to imagine these subbed out for our own rugby, cricket, and Olympic stories, sitting alongside Sport NZ’s Hall of Fame now is it?

It’s location at the iconic MCG provides it with a backdrop, a context, and a history, which simply wouldn’t exist in a central city location. Even in AFL-mad Victoria, it’s worth noting that AFL World was a short-lived central city sporting experience, much of which relocated to the museum at the ‘G.

—-

While there are some who will mourn the loss of the Hall of Fame in Dunedin, and some, with one eye flickering, who will fight for a new Christchurch CBD museum, they only continue a flawed model of celebrating New Zealand’s sporting heritage.

If we truly wish to embrace the place of sport in our cultural heritage, we need to elevate it beyond limited displays in Te Papa, beyond static stories in a railway station or twilight sport arena, beyond contextless shiny CBD attractions.

Much as I despair at the moniker, Eden Park has positioned itself as our national stadium and continues to expand on the experiences on offer. Opportunistic and ambitious, there’s an opportunity to be ambitious here.

The discomfort they may feel in Otago and Canterbury may spread to Wellington and Palmerston North, but, in the midst of all the debate, Sport NZ have a chance to embrace their central role, bring our sporting heritage together, and give this sports mad country a space to celebrate the contribution that sport, athletes, administrators, and, importantly, fans have made to defining Aotearoa.

Even if it is in Auckland.

Follow Jamie on Twitter